Translated from the Portuguese by Desirée Jung

Click here to download the text.

Sitting by a river, a poet was writing a poem on a wet clay brick. In his hand he held a well-sharpened stony blade, with which he sketched words and metaphors. A bird flying over the trees in the direction of the river became part of the theme that he wove into his lyrical text. After finishing a sequence of lines, he noticed that he had built a verse. At the end of the verse, the letters had already dried out to be eternalized in the stone for millennia. Line by line, verse by verse, the bird flew a poem over the trees.

Side by side, facing each other, the trees became a natural path—a road on which it was possible to walk with tranquility under the shade of treetops drawn on the clay ground. Through that avenue of grain-shaped branches—a winged boulevard—the bird exited the poem and landed on a green sunny leaf.

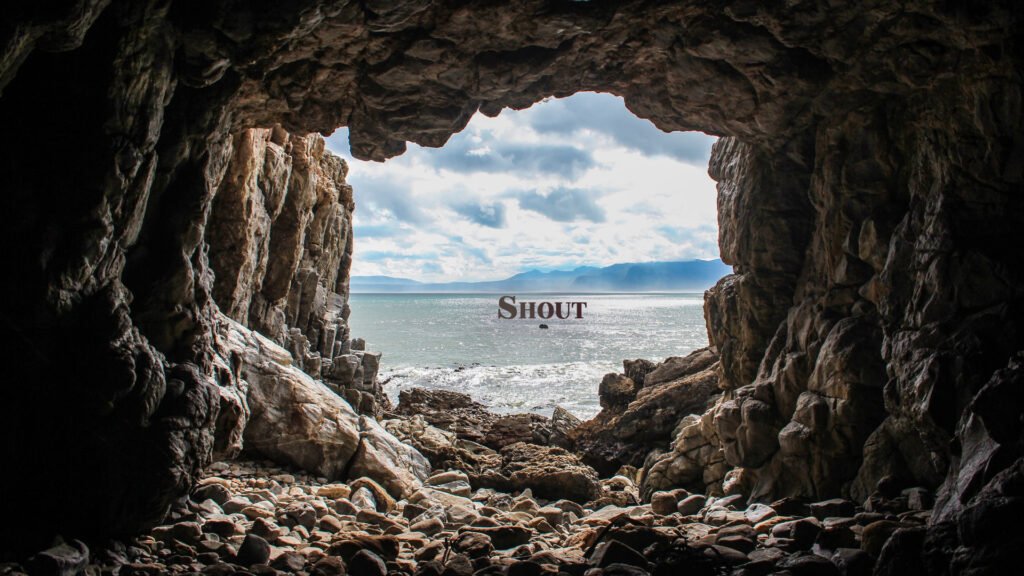

After a few minutes in the forest, the bird went back to the poet’s hand and, from there, pierced in low flight—in sound alliterations—the lines of the verse just sketched on the brick. The poet’s hand, which created metonymies inspired by a girl’s brown eyes, was the culminating extremity of a lyrically naked male arm. The poet translated his passion into poetry and hoped to give names to his feeling, yet he himself remained nameless: a shout.

Shout wetted the brick with the feeling that poured from his smitten heart without knowing that what he felt for the girl was called passion. Dropped on the brick, a tear was transformed into an allegory of the bird’s eye, which metamorphosed into the girl’s brown eyes.

Shout could not stop thinking about the girl, who inhabited the poem that he was writing on the brick. He had watched the girl’s sensual walk as she had exited her cave the previous day, and he had gazed at the empty hole and the small stone where she most certainly slept. He thought it would be reasonable to imagine that she was single—that no other hairy man, great-great grandson of a Neanderthal, was the owner of the girl, who insisted on taking charge of his thoughts and dreams. He had followed her discreetly from a distance and seen her cross three kilometres of a small grassy road, letting himself be scratched by rose-scented thorns planted by men and women who no longer inhabited the surrounding caverns.

Nomads showed up from everywhere more and more often. Shout, accustomed to his solitude, was bothered by the sudden insurgence of people who occupied the caverns, collected the fruit, fished from the river, and then disappeared into the nevermore of stones. He thought about the girl’s cave and about the axe, the cane, the lance, and the knife that she had left beside her chipped stone bed.

He also thought about the painting on the wall beside the stone, which was lit from a distance by the sun, and the smell of her body lingering in the Paleolithic air, which he tried to translate into the next line of the verse he was beginning to write. The attempt to pulverize the verse with the girl’s scent became real only when the bird, perceiving the poet’s anguish, flew into the cave and brought back in his beak the smell he was searching for. Then it flew straight into an ethereal rhyme.

The painting that Shout had seen in the girl’s cave looked recent—it might have been made only hours before—and it showed. The image was a very clear puddle of water with dots moving in the liquid. The dots were probably small orange fish jumping towards the surface before returning to the bottom. Beside the puddle, a woman, a child, and a man were lighting a fire. The smoke from the fire climbed up the wall to the ceiling of the cave—a grey thread that produced the sensation of heat, warming the interior of the grotto.

So the girl was not only beautiful but also sensitive—an artist—and if she were a nomad she probably wouldn’t return. But maybe she was not a nomad, since she was apparently alone and not part of a group, as nomads usually are. Or maybe she had been separated from her party and, before leaving the cave, had drawn the painting as a message for the other members of her group. Maybe she had only left to go hunting or to look for further inspiration, as her painting was not yet complete. Maybe it would continue to cross the ceiling to the opposite wall, decorating both sides of the dreamy stone where she slept.

As Shout followed her, hypnotized by the sensuality of her walk, her footprints became the starting anaphora in the unrhymed lines of the first verse of his poem. He climbed a tree and watched her walking gently from above, barefoot, trying not to step on the small worms that scurried into small holes when they sensed her beautiful feet approaching. From high up in the tree, he saw her lightly curled hair, which was brown like her eyes, streaming over her shoulders.

Behind a shrub, he saw the girl wearing a dress that was tied to her back and left her breast exposed. The dress was white and covered her back down one palm just above her knees. He ran through the bushes and overtook the girl from a distance. As he came closer he could finally give her face some attention, and he saw a pair of brown eyes under clear eyebrows and a fine nose. He also noticed that her well-shaped mouth was filled with pristine white teeth, and he used the image of her mouth in a poetic metaphor that transported the kiss he wished to give her into the flapping wings of an infinite now.

After walking three kilometres on a small grassy road, the girl lowered to pick three small branches from the ground, which she held firmly in her hands. Slowly she stood up and adjusted the branches in her arms, did a sensual turn, and began to walk back along the same road towards her cave. She walked as though parading on a runway. Could she have known that she was being watched? Were her footsteps part of a silent process of a non-verbal seduction? Finding it irrelevant to know whether the girl had seen him or not, Shout decided to thoroughly delve into the kilometres of the grassy road up to the ellipses of a decasyllable line petrified in the poem.

From the top of a small mountain, Shout noticed that the girl had dropped one of the branches. He wondered if she had dropped the branch on purpose, just so he could introduce himself and help her bring the branches to her cave. If that was her intention, it would be perfect, because all he wanted at that moment was to get closer to her and introduce himself, show her his shaped muscles, his manly beard, his white teeth, and his guttural voice.

However, unsure about the implicit messages she might be sending him and whether he could really trust his own lucidity, as his passionate torment might be overshadowing his reason, he chose to put the slippery eroticism of a dichotomic love between brackets and hold his will firmly on a branch hanging over the mountain. There he stayed until he felt the palm of his hand burn from the heat of the effort he made to continue hanging onto the branch.

When Shout looked down and begged his eyes to direct him towards the girl’s location, he experienced a deep disappointment: the girl was no longer there. The fallen branch was gone as well, as were her footsteps on the grass, and the brown of her eyes and hair had faded into a mad irony that took up two verses. As he sat by the river, he still thought about the destiny that the branches had given to her, and he asked the bird to fly her presence into the wetness of the chipped brick.

The girl, no longer in sight. The girl, no longer on site. She had unexisted herself completely on her way back to her cave. Her unfinished painting suggested a return in young ellipsis—maybe through ways that made her travel to a Cenozoic future. Shout, sitting by the river of tears produced by him since the previous day, wrote a poem that did not enable him to transform what he felt and lived into words. And, doing justice to the name he never owned, he looked at the title of the poem that he had just created and arched archaeologically in an arrow—an acute shout that traversed eras and eros of accurate errors.

Short Fiction by Anderson Borges Costa published in The Dalhousie Review.

Português

Português